What’s your dream? (or “How do you keep yourself going for 24 hours and what do you think about?”)

~ by Angela White

I have been invited to write about my recent experiences of pushing the distance over 24 hours running. In particular, to answer the question, “How do you keep yourself going for 24 hours and what do you think about?”

Undertaking any endurance activity is tougher mentally than it is on the body. I used to think 60:40 but now feel it’s more like 70:30. I discovered the sport six years ago and initially, for me, it was more about walking than running. It is a fascinating and revealing learning experience in which I still consider myself to be something of a novice. Each event gives me more information about myself and how I respond to the physical, mental and emotional challenges that it offers. Practically, that means that I can find myself re-framing many aspects of my approach to, and participation in, the next challenge.

Setting out on an event, my main objectives are to get to my destination quickly, safely and in the ‘best condition’ possible. The ‘best condition’ to me means that I am not totally dehydrated or underfed and, crucially, that I conduct myself in a way that enables my body to recover quickly afterwards. Each event itself is training and building upon what has gone before, and focusing on optimising recovery should, in my view, be as an important a part of the plan as running a good race.

This requires considerable preparation and planning beforehand. During the event, it takes a variety of skills, concentration and drawing upon a wide array of cognitive abilities.

As with any other mode of transport, running requires that you know your destination and your route to get there. You need to have enough fuel and water in the tank and a good idea of your rate of consumption and a plan as to how and when to fill up. Knowing where the ascents and descents are and having an idea at which point in the event you will need to tackle them is also helpful.

Alongside these basics is the need to manage temperature regulation. One thing I have learned is that, once I become fatigued, I don’t manage the cold and I have suffered from hypothermia on more than one occasion. In addition, well before that occurs, my leg muscles, particularly the iliotibial band and around the hip, stiffen and adversely affect my gait.

I’m therefore dividing my attention between a lot of factors and that’s before I’m looking at the detail of the road or trail surface to dodge potholes, rabbit holes, innocent-looking protruding rocks, puddles and piles of leaves covering hazards for the unwary to say nothing of being shocked and astounded at the behaviours and antics of other road users! These all present a need for constant visual attention and scanning of my immediate and upcoming environment both for navigation but as part of a need to rapidly process information on hazards to react quickly enough to avoid them. Developing good foot-eye coordination is also not to be underestimated.

Running on roads, in particular, places demands on auditory input and spatial awareness. Listening out for vehicles approaching from behind and making judgements on their proximity and speed and whether they have seen you and are taking care to modify their driving to respect you as a fellow road user. I am challenged by this as I am profoundly deaf in one ear having suffered from sensorineural deafness one afternoon seven years ago. Not only does this mono-hearing mean that I am unable to pinpoint the direction a noise is coming from but, it also left me with severe tinnitus on that side which is activated proportionately to constant noise such as wind, water, traffic, and conversation. This can become so loud that it masks the noises coming into my good ear and effectively renders me totally deaf.

Performing these functions for the most part occupy my thinking throughout each event. They feed into an outline plan for the event and dynamically modify it according to how the race unfolds.

Escape from Meriden, EFM

At midnight on Friday 17th November I commenced the last of a triad of 24 hour races in three months. This was Escape from Meriden.

In each of the first and second of these I had achieved over 90 miles but had finished each with some very nasty, painful blistering which had started some hours prior to the end. Unsurprisingly this had slowed me considerably. How do you deal with such things? It’s an issue I am still trying to work out and it is not very scientific. I have tried different shoes and a variety of cushioning and taping measures. I’ve spent a fortune on podiatrist and orthotics. The big challenge is testing what works as this can only be done by going out and running another very long way which, of course, you just don’t do in training. So essentially it is only during the next race when you find out whether something works – or not.

EFM is an event where you choose your own route. You have 24 hours to get as far from Meriden, the centre of England as you can, on foot. However, your final distance is measured as the crow flies so one needs to be as efficient as possible with route choice. My strategy was to head for a roman road and stick to that, hence the Fosse Way to the southwest was my plan.

Over a hundred competitors lit up like Christmas trees with a variety of head torches, bike lights and glow bands the colours of the rainbow gathered at the 500 year-old cross in Meriden excitedly awaiting the start. It was drizzling, the sort of wet that clings and penetrates slowly over time so you don’t appreciate how wet you’re getting. At the race director’s shout we were off, heading in multiple directions from the cross, many sprinting as if their life depended upon it. Finger on my Garmin, I pressed start to record my run but also to provide crucial feedback to guide me through it.

My next thought was to remind myself that I have a long way to go, ignore the pack. If anyone is on your route, you’ll be seeing them soon enough. I do a quick systems check: are my shoes and clothes comfortable, anything twisted or rubbing, head-torch giving me optimum view of the road surface. I check my race vest pockets, map top left, fluid top right, zips definitely closed. Check the map, right turn coming up and, yes about a mile along here I’ll meet the crew. This is a self-supporting event and you are allowed to have folks help you along the way. I was fortunate to have a series of three family members who would each leap frog me along my route. I had given each of them a set of marked maps, a provisional timing schedule together with what I thought I would need and where.

My Garmin vibrated on my left wrist alerting me to completion of the first mile. This was my cue to walk for a minute whilst drinking. I have employed this tactic a number of times and find it useful in long events to make sure I give time to hydration and fuelling but also a brief period to flush out toxic metabolites from the legs. I also believe an intermittent change of gait helps minimise complications of repetitive stress injuries such as anterior tibial tendinitis, suffered by so many endurance runners.

I passed the crew with a brief acknowledgement that all was well and that I’d see them at the next stop in five miles. Map in hand, I check the nav and took the next right turn and headed into the darkened lane. Most runners had dispersed and there were just four sets of flashing lights bobbing along the road ahead of me. From the map I was expecting to cross a railway line, and there it was, followed by roundabout and then turn left onto a lit road through a village. I was on this for a mile so switched my head torch off taking advantage of the street lighting to save battery.

As my Garmin buzzed for my attention I walked, ate and drank my way along. When running I tried to keep my pace to between 10 and 12 minute miles. I had a long way to go. The road surface was wet, lots of leaves, bad cambers, try to keep to the middle, fortunately not a lot of traffic in the lanes. Plenty of noise to sharpen the senses, rain drops from the trees on my jacket hood, scurrying of small animals in hedges whose nocturnal hunting I had disturbed and larger animals in fields who didn’t seem particularly alarmed by a mad human running by in the night.

I was aware it was cold, around 3 degrees and welcomed the hot chocolate the crew handed me along with a snack bar when we next met. I walked along drinking it. Every stationary moment might be rued in the final analysis should you have not optimised these transition times. As they drove at my pace past me ten minutes later I was again running and simply dropped the mug through the vehicle window.

My mind is constantly watching the nav, looking at the road surface and being aware of the environment to manage hazard avoidance, responding to my watch to fuel and hydrate and checking pace. 25 miles in and I was asked when I’d like my porridge to which I replied at the bottom of the next hill. A further mile on and I gladly accepted a hot porridge pot which I ate while slowly climbing the hill and handing the pot back as the crew passed me. The next stop was to be a handover between two crews.

My watch told me I was ahead of time by up to 30 minutes. Was this good or bad? I decided it was equivocal. 30 miles in 5 hours 30 minutes was ok at this stage. However, things can change rapidly. Within minutes as I climbed higher into the Cotswolds, the drizzly mist turned to thick freezing fog and visibility was reduced to just two or three feet. A systems check identified my legs around hips and thighs were rapidly stiffening and felt cold. I pushed on up the hill whilst planning what I needed from the crew to deal with this change of weather.

I was pleased to see my two crews had met up and I jumped into the awaiting van. I started to strip off my upper layers whilst asking for a very specific change of clothes and waterproofs. Another hot chocolate was ready and I took a few sips. With the luxury of dry baselayers, a warm mid layer and waterproof legs and jacket I quickly headed out with my hot chocolate and with the crew saying they’d keep closer during this weather.

The diffusion and distortion of the light from my head torch into the dense fog was disorientating and there was nothing for it but to walk carefully for two hours until night turned to day and I could see my way more clearly.

During this time I was calculating the impact that my slowed pace could have on the final outcome and what, if anything I could do to make up for lost time when I was running again, and came up with a plan.

As the daylight progressed, the fog was replaced by glorious autumnal sunshine which proudly displayed the next twenty miles of thoroughly enjoyable ‘undulating’ Cotswold countryside, looking every bit the 19th century oil painting, unspoiled by time.

As I warmed through I discarded my layers. I also deployed my plan, a ‘secret weapon’ I had been looking for an opportunity to try out. This was a caffeine shot made from concentrated green tea extract. I was interested to see the results. I had made sure to eat plenty during my enforced walk so I had ready calories to burn. I was pleasantly surprised by the results. I had expected a seriously high spike in energy and activity and a possible rapid burn out; instead it was more of a persistent gentle boost which saw me running steadily through this beautiful landscape all the while feeling how lucky I was and how alive I felt at that moment. I reached Compton Abdale, the fifty-mile point at 10am which meant I had regained my hopeful schedule. Furthermore, I was through the other side of Cirencester an hour up.

Fortunately, crew number three had been tracking progress and had headed up to take over from number two at Kemble in time for my arrival.

Things were beginning to hurt a bit now too. I tried to change shoes for the off-road Fosseway but my feet objected. I therefore moved straight into my second pair of road shoes which were a size bigger and different make with a wider toebox. It was a rather slower traverse of the Fosseway through to The Gib and into the second night. I had already blistered and taken a few minutes out to deal with the problem but I was taking a bit of time to adapt to the discomfort. The bitter wind did its best to be my undoing but my thermoregulation was well awry. Hardly surprising as by now I had been awake for 34 hours. However, rather than the usual hypothermia, I felt I was burning up so the cold was, in part, welcome.

A friend in the south had come out and cycled alongside for a few hours. It seemed rude not to try and move a bit more quickly as it was jolly cold and he was on the brakes going down the hills. I had another plan to use the secret weapon again but before I could allow myself to do that I needed to take some painkillers else I knew it would really hurt! I worked out what time I needed to take everything and to eat enough.

My aim, you see was not just to make the 24 hours but to reach 100 miles in that time. This was the first time in the whole race that I began to believe it might really be possible. I remained cautiously optimistic and focused on putting one foot in front of the other.

I picked up the pace on the steep descent into Bath and met up with the crew. A few seconds to do what was needed and then straight off again. Would it work again? Was I asking too much after this time awake?

“How long does it take to work?” Asked my friend. I wasn’t sure but started to run again. I know Bath well and didn’t need maps now. I discarded everything apart from base clothing and the tracker which I carried in my hand. What followed was an exciting caffeine-fuelled sprint across the city. I knew this would be my last chance to pick up speed and miles. I heard him say “Gosh, you’re rattling along”, and looking down at my watch I noted my pace was 8 mins 50 seconds. Just how is that possible when you’ve been up for 36 hours and in which you’ve run over 90 miles in the last 20 hours?

South of Bath, ahead on my route, were some hills which would prove a final test. My cyclist friend is the best company on these events, well experienced in endurance sports and has run with me on many occasions. He departed the far side of Bath after the first and biggest ascent with aching wrists but the knowledge he’d given me a huge morale boost.

I had nothing left to plan, I was not going to take any risks with my health with artificial stimulants – they’d proven their worth. I also wanted to sleep at the end of this.

A hundred was in sight but it was to be a battle. Mind over matter. I desperately wanted to sleep now, just to slump to the ground where I was and shut my eyes. It was so very hard. With next to nothing left in the tank physically and an enormous struggle mentally I forged my way onwards and upwards…….and down ……and up….. getting slower and slower…….mindful of each and every one of the 0.01 miles ticking up laboriously on my watch, and painfully in my being.

My son accompanied me on those last miles distracting me by reading out the many lovely and encouraging comments that friends had made on social media. I still wanted to sleep but my one thought was to get across that 100 mile barrier. “Are we there yet?”, he asked, I denied it and made sure that we continued to a bit beyond. The last thing I wanted was for Garmin to recalculate my route during its upload and take any of my hard earned century away from me.

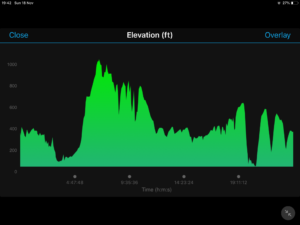

In the final analysis I achieved my personal objective and ran 100.2 miles with 6,332 feet of ascent. So far as the race itself is concerned, I covered 87.26 miles as the crow flew that night, came first lady, fifth overall and gained the Duke of York trophy for the most ascent.

![]()

There are highs and lows, deep dark lows, in any event but no matter how low it feels at the time, it’s just pain, or fatigue and it will pass whilst your achievement is there forever. Re-frame each and every physical struggle mentally and it will help you over it. It is rare in an event like this that there is nothing connected with the event to think about or to admire around me. On really tough physical bits I count and do maths problems. Sometimes the maths becomes quite complex and I don’t remember what the original question was but the point is, it doesn’t matter as it got me up that mountain, it gave the painkillers time to work, it took my mind off the weather or, for me, that scary bit of exposed mountainside.

I found this sport late in life but I think I’m more alive now than I’ve ever been. I’m curious as to just what is possible. It has taken a huge amount of hard work. I’ve had many disappointments, broken bones and very low points. I have also met some lovely people and made some great like-minded friends. I’ve met and know some very remarkable people, all who’ve worked to achieve their own ‘impossible’. In a few short years I have pushed my own boundaries well beyond my imagination – despite loud protestations from well-meaning friends. Never put limits on your dreams nor let anyone else do so for you. If I had listened to them, I wouldn’t be living life now.

“You’re never too old to set a new goal or dream a new dream” said C. S. Lewis

What’s your dream?

Thank you for reading and I’d love to hear what strategies you use to keep you going.

Angela White

December 2018